The world mourns Muhammad Ali; and rightly so. How many sportspeople will have the eulogy at their memorial service given by a former American president? But that is what is about to happen today in Louisville, Kentucky. At his peak Ali was one of the most famous and most recognisable people on the planet; he was loved especially here in the UK, partly for his boxing and partly when we saw his sharp wit on his famous interviews with Michael Parkinson. He may have been untutored but the intelligence was ferocious.

The world mourns Muhammad Ali; and rightly so. How many sportspeople will have the eulogy at their memorial service given by a former American president? But that is what is about to happen today in Louisville, Kentucky. At his peak Ali was one of the most famous and most recognisable people on the planet; he was loved especially here in the UK, partly for his boxing and partly when we saw his sharp wit on his famous interviews with Michael Parkinson. He may have been untutored but the intelligence was ferocious.

I’m not writing about his boxing, because it’s all been said by people very much more qualified than I. This is about his positive attitude to life and to events, which must have been a contributory factor to his success

We cannot all be boxers, or elite sportsmen of any kind. We can’t all have the ability to improvise humorous replies as fast as he could. But if you ever have to prepare for a potentially stressful occasion – a speech, a stage performance, a difficult meeting – there are two important and practical things you can learn from him.

Self-talk

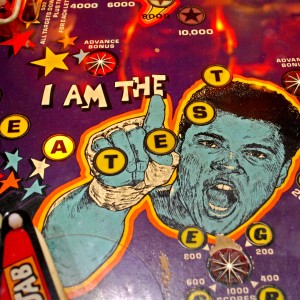

Firstly, and famously, we remember how he talked about himself: “I am the greatest!” He started doing this before he became world champion. Later in life, when questioned about that phrase, he said: “yes, I said I was the greatest … even before I was.” Some people – especially here in the UK – put this down at first to arrogance but now, I think, we know better than that.

In an interview, Ali said he first got the idea from a wrestler called Gorgeous George, with whom he shared a platform at a promotional event early in his career. Gorgeous George was not a particularly successful wrestler but increased his popularity by telling jokes and saying “I am the greatest!” Ali heard that and immediately began to copy it.

What’s the lesson for us, particularly if we come from a more self-effacing culture? We probably won’t say “I’m the greatest”; but we could at least avoid the ‘self-sabotage’ of saying to ourselves and others: “I’m not much good at XYZ.” If you tell yourself something often enough, your subconscious mind will start to believe it, whether or not it’s true. That’s something that the young Cassius Clay understood very well.

Predicting and visualising the outcome: creating ‘future history’

So Ali was the greatest, and he told himself so. He also used another very specific method of training his subconscious to expect the best, by creating what he called his ‘future history.’

When a new fight was arranged and he attended a press conference to announce it, immediately afterwards he would excuse himself, go up to his hotel suite, draw the blinds, and just sit down and relax, breathing deeply, and create a mental picture of the end of the fight. More than just creating a picture: he even used to predict in which round he was going to win; he would get into that level of detail.

And he would create this picture of the end of the fight: opponent flat on his back; referee raising his own arm; Harry Carpenter climbing through the ropes with a microphone. Then he would freeze-frame that picture and carry it around for the next two or three months until the day of the fight. That was his version of what’s sometimes called ‘creative visualization’ but I prefer the term he himself used: ‘future history.’

So how could Ali’s method be tailored to your needs? What’s your equivalent of that knockout moment? This is where you go back and remember what is your purpose in giving the speech, or whatever performance you have to give. Then you can create your own picture of a successful outcome – by your own definition; nobody else’s. For example, if you’re speaking at a wedding, your picture could be of the smiling bride appreciating what was said, an enthusiastically applauding audience, etc. Those kinds of mental pictures can help you anticipate the day ahead with pleasure rather than dread.

A man who transcended his sport.

Me? I was never a fan of the brutal sport of boxing; but I was always a fan of Muhammad Ali. Like everyone else on the planet, I watched him every chance I got, whether he was fighting or just talking. He dominated his sport, changed attitudes to minorities, and lit up our lives.